My first encounter with Sir Philip Sidney wasn’t The Defense of Poesy. It was the opening sonnet of Astrophil and Stella which I read at A Level. My English teacher printed it on red paper and so it is indelibly fixed in my mind with a red background.

The first in the series addressed to the narrator’s beloved, ‘Stella’, the sonnet is more about writing and creativity than about love. For Sidney the writing process is a viscerally physical and even violent experience expressed in harsh, plosive verbs: “Biting my truant pen, beating myself for spite”. The refusal of his pen to bend to his will is ruefully funny as well as resonant for any writer.

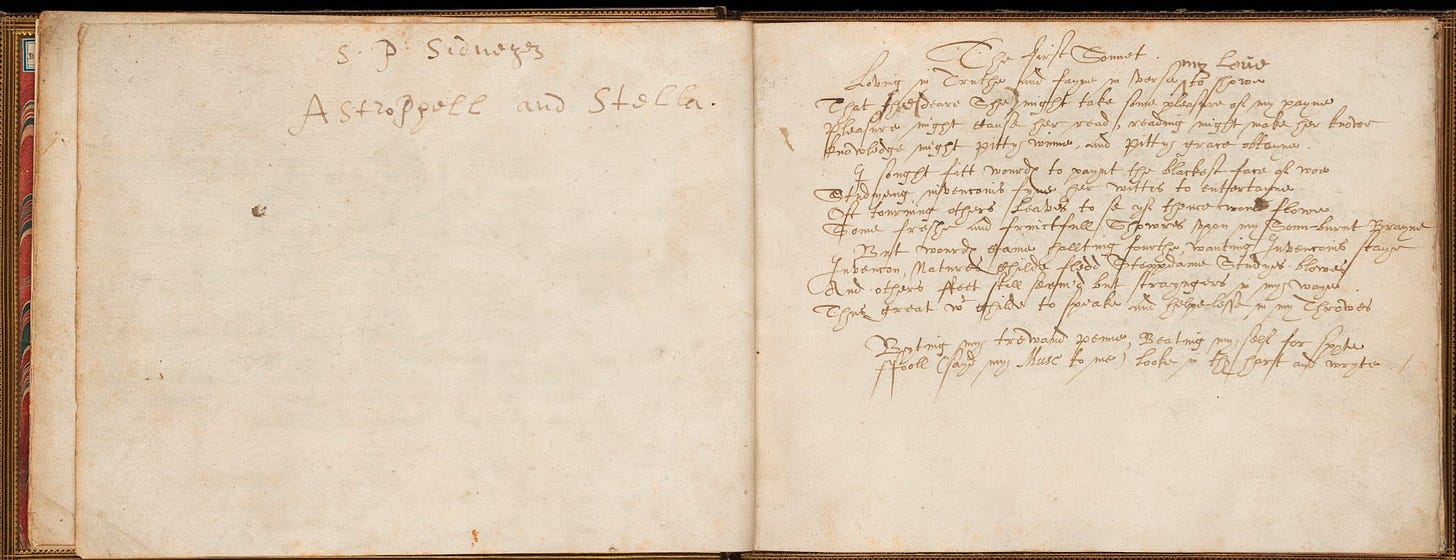

Astrophil and Stella circulated in manuscript in Sidney’s lifetime. The image above is a fair copy in Sir Edmund Dymoke’s handwriting from 1591 (now in the University of Edinburgh collection). Sidney seems to have been reluctant to let it go further than his immediate circle. Perhaps the attachment to manuscript also says something about the relationship between poetry and the physical act of handwriting. In the difficult process of getting words onto a page, the hand has to be in contact with the pen, the ink to mark the paper.

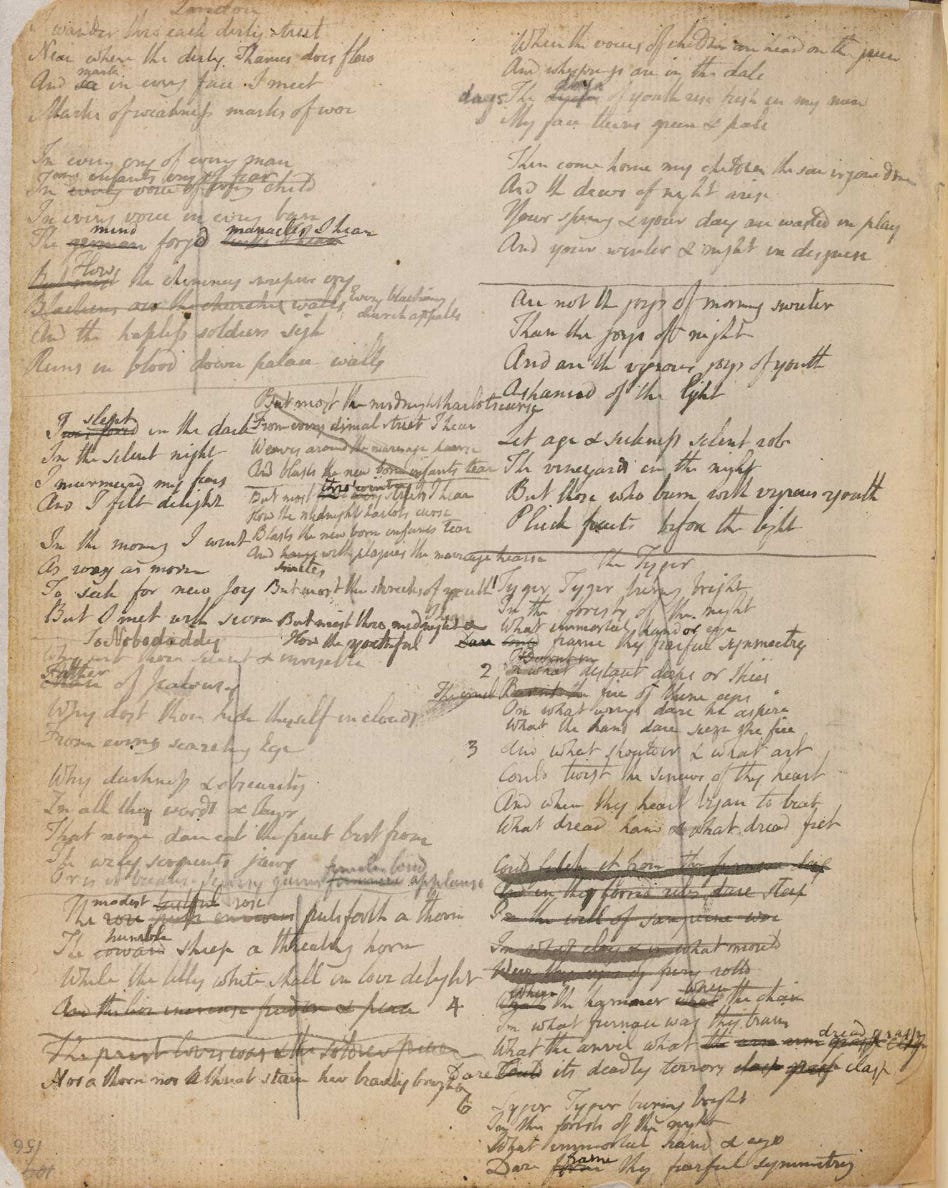

I actually had to give up writing with a fountain pen at a certain point due to my terrible habit of biting it and then accidently letting it fall from my mouth to the floor. I spattered a good deal of ink and wrote a lot with cracked nibs before finally realising it was best to use a fibre tip. However, I continued to write by hand — all my notes up to and including pretty much everything I read for my PhD were handwritten and I always planned essays or chapters by hand before typing up a draft. There’s something that happens with the press of pen to paper, an embodying of the written word, that can’t be replicated with a keyboard and screen. When I look at a manuscript like William Blake’s Notebook (image above), it’s impossible not to be moved by his handwritten drafts. The poem in the bottom right corner is “The Tyger” — look at him numbering the verses to decide which order they should go in.

Eventually, I succumbed to typing my notes because my full-to-bursting lever-arch folders were too unwieldy. Now, of course, most of my day-to-day writing is typed on my laptop.

Yet, I still start poems in a notebook. Unlike the vanished rewritings of this piece, the inky paper marks the process of the truant pen; the mistakes, crossings-out, warts-and-all record of failures is there, but so is the first, irreplaceable moment of inspiration.

I love this and I love the 'pregnant' imagery and ideas in Astrophil and Stella. The outcomes of pen to paper are undoubtedly different from anything we type. There is something in the sensory experience of handwriting, as much as in its cognitive dimension. Unfortunately it's impossible to ever tell if the same poem would have been different if started in a different medium.

How fabulous to be able to see Blake's work in manuscript like this! Great proof that nothing comes out perfect the first time for anyone. My students still struggle with this idea expecting perfection and then refusing to try to improve by drafting. Seeing is believing! And writing is rewriting. Yes, I do most of my first drafts of poetry by hand. Thank you for this post!