Welcome to all my new subscribers. It’s lovely to have you here. And thank you to everyone who continues to read Ink Wasting. Spring is peeking through the sludge and clutch of mud season so brighter days are ahead.

“In order to read poetry rightly, one must be in a rash, extreme, a generous state of mind…” — Virginia Woolf

I find that writing creatively comes in waves and winter tends to be a fallow time. If I’m not writing poetry, then I like to be reading it: going back to old favourites and finding new inspiration. It has been a real delight lately to encounter new poetry on Substack as well as dipping into the wealth of literary magazines online. But there is nothing quite the same as immersing oneself in a poetry collection. It is in the gathered poems of a collection that the voice, tone and style of the poet — what makes their writing theirs — truly flourishes. It’s the reading equivalent of listening to an album all the way through rather than highlights on a Spotify playlist. You can listen to “Go Your Own Way” by Fleetwood Mac on its own but the brilliance of the track is best heard as part of Rumours.

Virginia Woolf’s essay on reading looks at ways to read different genres and for poetry she posits “one must be in a rash, extreme, a generous state of mind…” Poems may be brief, but often their very brevity requires of the reader more focus, more concentration of intellect, more power of imagination. As Woolf suggests, there is an “exaltation and intensity” to reading poetry because more than any other written form we are required to bring our own interpretation to the page. In a collection, we must do this time and time again, considering not only the meanings of one poem but the possible connections across a range of poems. This is why, I think, that reading a collection of poetry requires returning many times — and therein also lies the reward.

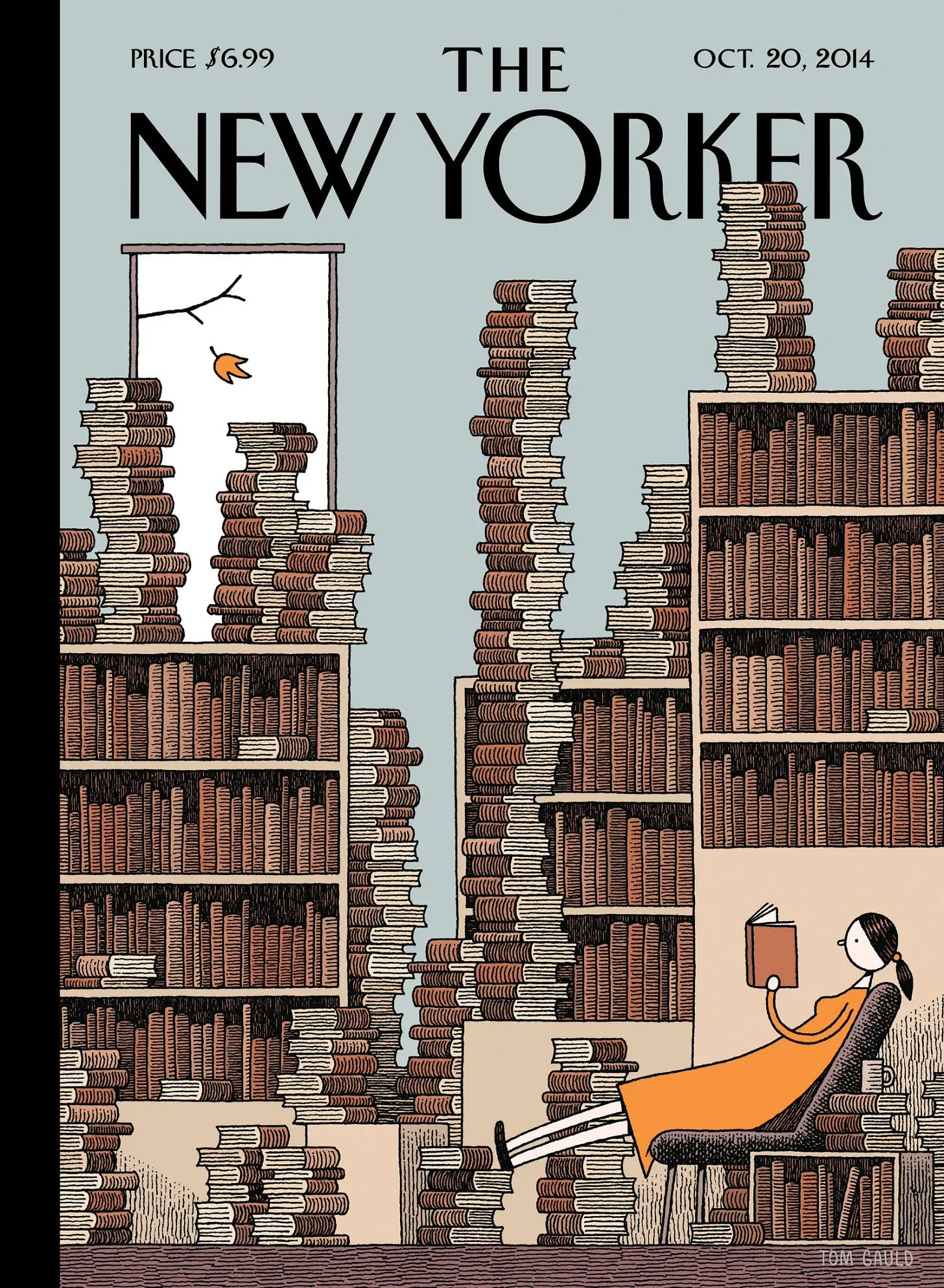

“The Fall Library” New Yorker cover image is pretty much my ideal of reading for any season. I love reading fiction and I consume narrative of some kind on a daily basis. But I have to admit, it’s not like that with reading poetry. I can’t just pick up a collection any time and get stuck in. Even individual poems that I come across on Substack or elsewhere, if I really want to take them in, I have to read them and then come back to them. Even though they may be shorter, it takes longer because this type of reading is not purely about consumption. It’s slow reading, an art in itself and one that is making a comeback in our fast-paced times.

Jonathan Bate uses the analogy of eating to describe the experience of reading poetry:

“Most of the time, we fill our minds with words that are the equivalent of fast food. Poetry is slow mind food, real nutrition for the soul."

The idea of fast food certainly fits many of our reading experiences these days: quick sugar hits that give us a momentary high but are ultimately unsatisfying and don’t stay with us. I like the idea of poetry as “slow mind food”, something that provides lasting nourishment, something that we need to ruminate over and digest like we might longer literary fiction. On the other hand, I want to resist the idea of poetry as another form of media we can simply devour, a delicious morsel for our consumerist society to swallow. Better than food, poetry can sustain us for years. Incidentally this is one of the intangible rewards of teaching it — teenagers may not understand Sonnet 116 right now, but maybe, maybe in ten or twenty or thirty years, they will come across it again and think — oh, yes, I see now. Reading poetry is not about chewing through content but layering interpretation and meaning through repeated re-encountering and attentiveness to language, structure and form.

In “Diving into the Wreck” Adrienne Rich considers the difficulties and dangers that attend deep reading:

First having read the book of myths,

and loaded the camera,

and checked the edge of the knife-blade,

I put on

the body-armor of black rubber

the absurd flippers

the grave and awkward mask.

I am having to do this

not like Cousteau with his

assiduous team

aboard the sun-flooded schooner

but here alone.

The power of the metaphor of deep-sea diving lies in the concrete images Rich supplies accompanied by the terse reminder “and besides/you breathe differently down here.” For me, it resonates with the ways in which reading poetry specifically is desirably difficult. It requires the “body-armor” and “flippers” to get us down to the deep, the tools of understanding literary techniques and above all, it requires from us a different mode of being.

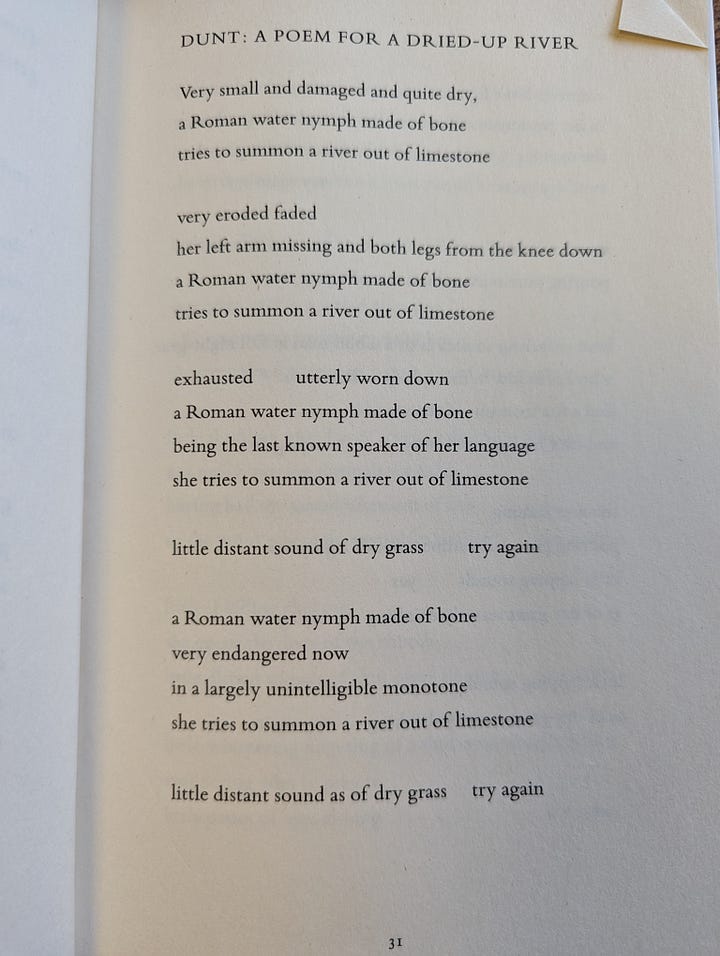

For a truly other-worldly deep-dive poetic experience, I’ve been reading Alice Oswald’s Falling Awake (2016). Even the oxymoron of the title shudders the reader to a standstill with the jolt of something both new and familiar. Oswald’s subject is nature, infused with human emotion and shot through with myth. The image of falling, especially falling water, is one Oswald opens with in “A Short Story of Falling” and returns to repeatedly in this collection. Speakers or protagonists in her poems are overlooked aspects of nature or fallen, lost mythic figures. The narrative voice of rain in the first poem offers a “story of the falling rain/that rises to the light and falls again” with slipping flashes of sunlit water that are recalled later in “A Rushed Account of the Dew”. The brief almost-life and unremembered memories of rain and the dew, which clasps leaf “with a liquid cufflink” only to disappear again, become a light that sheds on the story of Orpheus in “Severed Head Floating Downriver” where the musician-poet is both transformed “already forgetting who I am” and metamorphosed into another element “my voice being water”. In “Dunt: A Poem for A Dried-Up River”, Oswald poignantly offers the narrative of “a Roman water nymph made of bone” summoning a lost river in a series of stanzaic repetitions that become almost like an incantation: “try again…try again”. Here the dry sound of grass seems to echo the lost sound of water which is also the “little shuffling sound as of a nearly dried-up woman” who is the nymph and the river together. The landscape is a dream-like one yet Oswald hints at the environmental degradation of the present. The river and/or nymph is “victim of Swindon/ puddle midden/ slum of over-greened foot-churn”. There is a brief, heart-rending memory of “the days of better rainfall” when the banks flooded before the final reminder that the “beautiful disused route to the sea” is no longer a river.

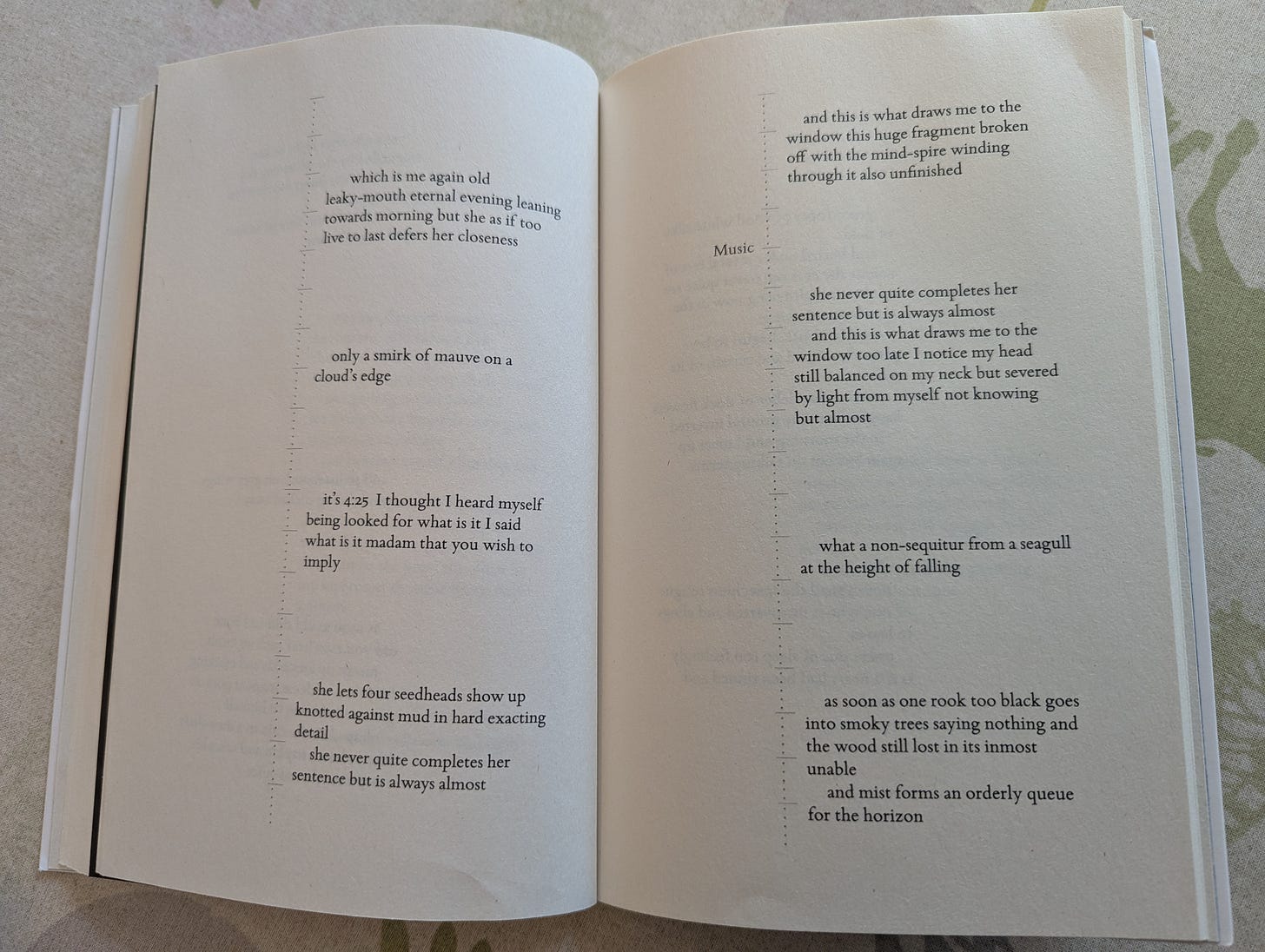

The final section of Falling Awake is an experimental dramatic monologue, “Tithonus: 46 Minutes in the Life of the Dawn” based on the mythical story of Eos (Dawn) and Tithonus, a Trojan prince. Eos fell in love with Tithonus and asked for him to be made immortal but forgot to ask that he never grow old. Oswald brilliantly imagines the five thousand year old Tithonus babbling to himself as dawn appears “not/ yet gone here I go again”. The poem appears to the right of a timeline or stave incrementally counting down the minutes of dawn. The rambles of Tithonus, like the voices of nymph of “Dunt” and Orpheus’ severed head, gather meaning as they roll on, deliberately turning back to almost the same words and phrases. There’s a sense here of the rumination of the traumatised speaker cycling through the same tired thoughts. Tithonus observes “the sound of everything repeating” reminding us of his daily futile half-life still yearning to communicate with dawn, repeating that “she never quite completes her / sentence but is always almost”. The stave occasionally posits “Music” on the left but we do not hear the voice of Dawn, until perhaps the final poem, separated by blank pages from the end of Tithonus’ monologue in fading out grey-scale type might be her “never quite/ / appearing”.

At the same time, as Tithonus’ cyclical thoughts, “the same old grief”, come into contact with the natural world, (almost) new (almost) thoughts arise as he witnesses nature going about its business — grasses, beetles, a chaffinch, a spider, midges forming the reminder that “the very/ moment is itself a movement”. With all its repetitions, the poem never stands still but becomes itself “the makeshift character that/ springs from speaking and looking on…” Tithonus’ gradual fall into and out of consciousness, like the fall of dew, like the almost-erased characters of Orpheus and the Roman nymph, is so intersected with space on the page that the reader inhabits the contradictory feeling of being weighted while in mid-air, simultaneously falling and/or flying without even knowing which one is experiencing. Perhaps, now I think about it, such ambivalent falling is another metaphor for the encounters of slow reading. I cannot imagine that my reading of Oswald is in any way complete and this collection is one I want to return to over and over again.

Virginia Woolf’s essay “How Should One Read A Book” is in The Yale Review.

As I muse on ways of reading, it turns out I’m not alone. For more on slow reading in the digital age see:

Michael S. Rose on “The Subversive Art of Slow Reading”

Julian Girdham on Thomas Newkirk’s The Art of Slow Reading and Maryanne Wolf and Cognitive Patience

For a beautiful account of creative wanderings through sunken wrecks, I highly recommend:

Artemisia Writes on “from echo-chambers to eco-systems: museums for a vanishing world”

This is surely now a ready-to-go talk for a wider audience! Thank you also for recommending my own ink-wasting labour of love ❤️

Wow - some incredible collections here, many of them new to me. This winter has certainly been a fallow time for my writing. 💚🌿